| Home > Living In China |

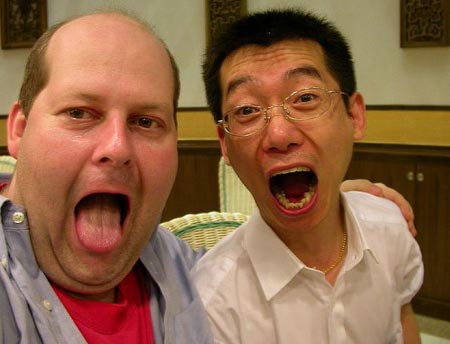

Ways to Make Chinese Friends

Conveniences afforded by rapid modernization have made it possible for the average foreigner to get by (barely) in China without speaking a word of Mandarin. Translation software and supermarkets make survival without Chinese friends possible. Cloistered in work situations unconducive toward interacting with locals, it is possible to live in China without having a single Chinese friend. Some are perfectly happy to spend all their leisure time with fellow expats. A large proportion of foreigners, however, come to China to gain cultural experience and this cannot be attained in a friend-less vacuum.

Having a hard time making Chinese friends? Here are some possible reasons why, along with suggestions on how to bump up your chances at friendship in China.

Friendship defined, Chinese-style…

Before writing all locals off as insincere opportunists, try seeing friendship from their eyes. Chinese tend to use the word "friend" rather loosely – for everything from colleagues to casual acquaintances. In a name-dropping, guanxi-based society, contact details are usually requested within minutes of making an acquaintance. Following months of silence, a local acquaintance is capable of striking up a conversation like an old friend. Although, to be fair, networking is a perfectly legitimate pursuit back home. Soulmate-type friends do exist in China – you just have to look harder for them. Having defined "friend", let’s move on to the causes of friendlessness.

Reasons why making Chinese friends can be difficult

1) Effect of nationality on "friend-ability"

Growing affluence in China means a growing appetite for the exotic and the imported, friends included. A foreign passport can work like a friend-magnet, at least until the novelty has worn off. It can also work the other way, with the recent rash of incidents involving foreigners behaving badly in China causing a significant amount of backlash and anti-foreigner sentiment. Not to mention that most Chinese already possess insecurities toward how foreigners view them. Lastly, not all foreigners are created equal. People from Western countries usually enjoy the warmest welcomes (sincere or interested), while foreigners from developing countries could find themselves looked down upon by locals. Relationships between countries are ever fluid and unpredictable, hence the effect a foreigner’s nationality may have on locals is something that is beyond one’s control. But having knowledge of how locals view people from different countries is useful in getting to know how they think.

2) Cultural differences

Chances are, China differs from your home culture on at least four out of five of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions. Cultural differences are employed by both Chinese and foreigners to explain everything from differing service standards to political systems. Specifically, Chinese concepts of guanxi (connections) and mianzi (face) are often bewildering to those from meritocratic societies. Neglecting to build networks and failure to give face (adequate respect) are potential friendship landmines.

Those taking a long view of their stay in China would find going a step back and understanding Chinese history a worthwhile investment. Chinese are understandably proud of their "5,000 year-long history", which significantly and indelibly shapes current thinking and behaviour. In ancient China, guanxi did not have its current negative connotation as people worked hard at maintaining relationships. Recent history has eroded traditional relationships among Chinese as they continually seek immediate connections – a.k.a. the we’ve-met-once-therefore-we-are-friends phenomenon. A Chinese "friend" who seemed so warm and effusive in the first few meetings suddenly disappears after finding out his or her target’s financial or social position.

3) Language barriers

Adding to the seeminly insurmountable cultural barriers are language barriers which serve to widen the chasm between foreigners and locals. Especially considering that Mandarin Chinese is not an easy language to master for those learning it as an adult. Even fluent Mandarin-speakers meet accent discrimination in parts of China less accepting toward differently-accented Putonghua. Chinese looking to make foreign friends that can be used as language partners are not hard to find, but not every foreigner relishes being a free language-practice target. In rare cases where true friendship subsequently develops, the road is more often than not fraught with lost in translation potholes.

4) Not doing as the Chinese do

On a more mundane level, culture affects day-to-day activities like eating habits to leisure pursuits. Being in China but unable to do as the Chinese do could jeopardize chances at friendship in regions where locals are less tolerant of "Western" preferences. In places where cuisine options are more extreme, like hot and spicy Sichuan, not every foreigner is willing and able to join in their newfound friends’ weekly hotpot sessions. Ditto with mahjong and karaoke sessions. Being perceived as "different" could mean "not friendship material", especially in inland parts of China less exposed to foreigners.

5) Being technologically hip in China

Policies in China have also affected communication methods. Young working adults favor QQ and Weibo over Skype and Twitter; Tudou and Youku over YouTube. Sure, many scale the Great Firewall, but such expeditions are usually confined to satiating curiosity on YouTube, news sites and the odd Skype session with foreign friends. Suggesting that a local friend sends you an email will not go down as well as leaving a message on QQ.

6) Sometimes, the answer lies within

So far, the discussion had been confined to environmental factors, but to a large extent, friendship also depends on the individual. The workplace is a good place to develop friendships due to the hours spent there but some workplaces, like universities, may deliberately separate local and expatriate staff. Choice of leisure activities is also another factor. For example, friendships forged in pursuit of common interests are typically deeper than those made under the strobe-lights of the disco. Lastly, the clichéd adage, "if you want a friend, be a friend" applies. Being more outgoing helps in drawing out locals who tend to be more self-conscious and introverted, as effusive ones often turn out to be shameless opportunists.

To increase chances at friendship in China

- Get on a local social-networking or microblog site like QQ or Sina Weibo – especially helpful to build networks with young working adults.

- Remember, when using humor, that Lost in Translation is not just a movie – at best, efforts at lightening the atmosphere could fall flat; at worst, they could prove offensive.

- Try not to decline an invitation without very good reason for doing so.

- Pursue a hobby that locals would engage in, such as Chinese painting or joining a gym. Joining an English corner or attending a local religious group are other possibilities.

- Avoid "sensitive" or controversial topics on the first few meetings, especially politics or news that cast China in an unfavourable light. Being critical of China is something of an art form in and of itself!

Custom

more

moreWeb Dictionary

Primary&secondary

Beijing National Day School

Beijing Concord College of Sino-Canada

Brief Introduction of BCCSC Established in the year 1993, Huijia School is a K-12 boarding priva...Beijing Huijia Private School

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate